The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, and interconnected digital technologies has fundamentally altered the landscape of civil liability across Europe and beyond. Traditional legal frameworks, built upon centuries of precedent governing tangible products and human decision-making, now struggle to accommodate the complexities introduced by algorithms that learn, adapt, and operate with minimal human oversight. As these technologies become embedded in critical infrastructure, healthcare delivery, transportation systems, and everyday consumer products, the question of who bears responsibility when something goes wrong has become increasingly urgent. Regulatory bodies across the European Union have responded with comprehensive reforms designed to modernise liability regimes whilst balancing innovation with consumer protection. Understanding these evolving frameworks is essential for manufacturers, developers, legal practitioners, and policymakers navigating this transformative period.

Emerging liability frameworks for artificial intelligence and machine learning systems

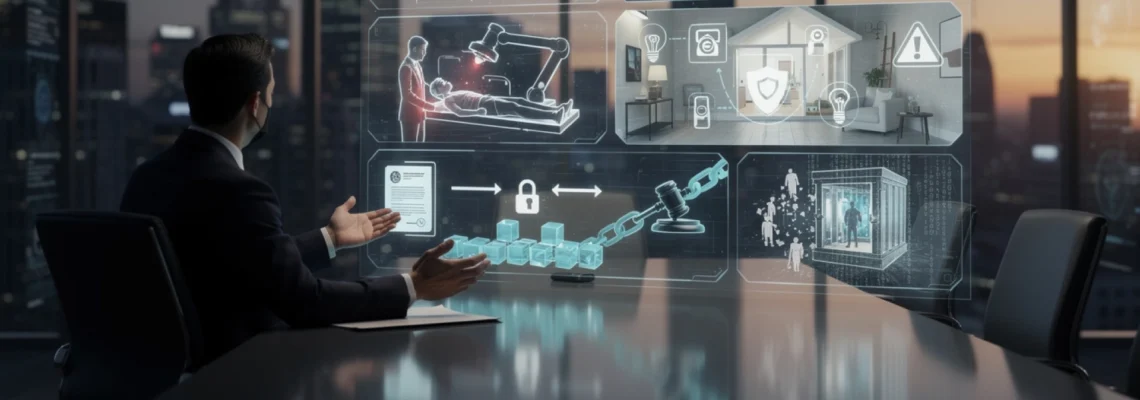

The European Union’s legislative response to artificial intelligence liability challenges represents one of the most ambitious attempts globally to establish comprehensive accountability mechanisms for emerging technologies. The convergence of the revised Product Liability Directive and the AI Act creates a dual-layered regulatory structure that addresses both the unique characteristics of AI systems and the broader implications of digital product defects. This framework acknowledges that traditional fault-based liability rules, which require victims to prove wrongful conduct, causation, and damages, are ill-suited to handle claims arising from autonomous systems whose decision-making processes remain opaque even to their creators.

Product liability directive reform and AI-Generated harm attribution

The revised Product Liability Directive, approved by the European Parliament in March 2024, fundamentally expands the concept of “product” to encompass software, digital manufacturing files, and AI systems whether standalone or embedded within physical devices. This expansion addresses a critical gap in the original 1985 Directive, which focused primarily on tangible goods and left considerable ambiguity regarding liability for purely digital products. Under the new framework, software updates, algorithmic modifications, and even self-learning capabilities can render a product defective after its initial market placement, creating ongoing liability exposure throughout a product’s operational lifecycle.

The revised Directive introduces several mechanisms specifically designed to address the evidential challenges posed by complex AI systems. Courts may now order disclosure of relevant technical information, including training data, model architecture, and decision logs, when plaintiffs demonstrate reasonable grounds for suspecting defectiveness. This disclosure power extends even to proprietary information and trade secrets, though courts must balance transparency with legitimate business interests. Significantly, if defendants fail to comply fully with disclosure obligations, the law presumes the product was defective—a powerful incentive for comprehensive documentation practices throughout the development process.

Algorithmic accountability under the EU AI act’s Risk-Based classification

The EU AI Act establishes a risk-based regulatory framework that categorises AI systems into minimal, limited, high, and prohibited risk tiers, with compliance obligations proportionate to the potential for harm. High-risk AI systems, which include those used in critical infrastructure, law enforcement, essential services, and safety components of regulated products, face stringent requirements encompassing continuous risk management, robust data governance, technical documentation, event logging, transparency measures, human oversight mechanisms, and cybersecurity protections throughout the system’s lifecycle.

What distinguishes this approach is its focus on the intended purpose of the AI system rather than solely its technical characteristics or actual deployment context. An AI system designed for use in border control or creditworthiness assessment automatically qualifies as high-risk regardless of whether real-world deployment presents elevated dangers. This classification methodology creates potential compliance burdens for developers whose systems may be adapted for high-risk applications by downstream users, necessitating careful contractual allocations of regulatory responsibility within supply chains.

Vicarious liability challenges in autonomous Decision-Making systems

Traditional vicarious liability principles, which hold employers responsible for the wrongful acts of employees performed within the scope of employment, confront conceptual difficulties when applied to autonomous AI systems. Can an algorithm be considered an agent of its deployer? At what point does machine autonomy sever the causal chain linking developer or operator conduct to resulting harm? The revised liability framework addresses these questions by imposing joint and several liability throughout the supply chain for entities whose contributions influenced the defective product, including those who substantially modify systems through updates, retraining, or integration with other components.

This extended liability net captures not only original manufacturers but also integ

ors, deployers, cloud service providers, and even integrators who adapt general-purpose AI for sector-specific use. In practice, this means that an enterprise deploying an AI-driven decision-support tool cannot simply shift all blame to the software vendor when harm occurs; courts will examine whether the deployer implemented appropriate oversight, validation, and monitoring mechanisms, and whether they complied with both regulatory duties and contractual obligations concerning safe use.

At the same time, the EU’s emerging civil liability regime stops short of recognising AI as a separate legal person. Liability remains anchored in human and corporate actors whose design choices, training practices, data governance, and operational decisions shape the behaviour of autonomous systems. For organisations, this calls for robust internal governance structures—clear accountability lines, audit trails, and documented risk assessments—so that when an AI system makes a harmful decision, it is easier to identify which human-controlled process failed. Without these measures, companies may find themselves facing expanded vicarious liability exposure based on the presumption that insufficient oversight allowed an autonomous system to operate dangerously.

Causation standards in black box AI: establishing breach of duty

Perhaps the most difficult element in AI-related civil claims is proving causation where complex, non-linear models operate as opaque “black boxes.” Traditional negligence analysis assumes that we can trace a relatively clear chain of events from breach of duty to damage. By contrast, deep learning models may incorporate millions of parameters, dynamic feedback loops, and data-driven behaviours that are not easily reducible to human-readable explanations. This opacity raises a practical question: how can a claimant show that a particular design choice, data flaw, or oversight failure more likely than not caused the harmful output?

The revised Product Liability Directive and the proposed AI Liability Directive respond to this evidential challenge by easing the burden of proof in particularly complex AI scenarios. Courts may presume defectiveness or a causal link where claimants demonstrate that: (i) the AI system failed to comply with mandatory safety or regulatory requirements; (ii) the type of harm suffered is typically consistent with that kind of non-compliance; and (iii) technical complexity makes it excessively difficult for the claimant to provide granular proof. In such situations, the defendant must rebut the presumption by showing that another cause intervened or that the system’s design and operation were in fact compliant and safe.

From a risk management perspective, these evolving causation standards elevate the importance of rigorous documentation. Organisations that can produce detailed model cards, testing reports, incident logs, and change histories are better positioned to demonstrate that they exercised due care and that any harm was not causally linked to their breach of duty. Conversely, sparse documentation can function like an evidential vacuum, inviting courts to infer that black box opacity masks underlying negligence. For developers and deployers alike, treating explainability and traceability as core compliance requirements—rather than optional technical luxuries—will be essential in mitigating liability risk.

Autonomous vehicle accidents: apportioning fault between manufacturers and users

Autonomous and semi-autonomous vehicles provide a vivid illustration of how technological innovation disrupts conventional negligence and product liability doctrines. Collisions involving driver-assistance systems like Tesla’s Autopilot, advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), and higher-level automation raise difficult questions about the respective responsibilities of human drivers, vehicle manufacturers, software developers, and component suppliers. Is a crash primarily a matter of driver error, an underlying product defect, or a failure to provide adequate warnings and user training?

Across jurisdictions, courts and regulators are gradually shaping a hybrid approach that blends traditional traffic law concepts with product liability principles adapted to autonomous technology. As automation capabilities expand from lane-keeping and adaptive cruise control towards full self-driving functionalities, we see a progressive shift in expectations: drivers are no longer merely users of a tool, but supervisors of a quasi-autonomous system whose behaviour they may not fully understand. For companies operating in this space, clear communication about system limits, realistic marketing claims, and robust event-data recording capabilities are becoming crucial elements of liability management.

Tesla autopilot case law and evolving negligence standards

Litigation surrounding Tesla’s Autopilot and “Full Self-Driving” (FSD) features has served as an early test bed for allocating fault in semi-autonomous driving incidents. In several high-profile cases in the United States, plaintiffs have alleged that Autopilot’s design was defective, that Tesla overstated the system’s capabilities through marketing, or that warnings about the need for constant driver attention were insufficient. In parallel, regulators such as the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) have opened defect investigations into crashes involving ADAS features, focusing on driver monitoring, system disengagement behaviour, and human–machine interface design.

Court decisions and settlements in these cases suggest a nuanced trend rather than a simple manufacturer-versus-driver dichotomy. Where evidence shows the driver ignored clear warnings, failed to maintain hands on the wheel, or misused the system in ways expressly prohibited, contributory or comparative negligence findings are likely. However, where system design arguably encouraged over-reliance—for example, through naming conventions like “Autopilot” or user interfaces that create a false sense of full autonomy—courts may be more willing to attribute fault to the manufacturer. In effect, negligence standards are evolving to consider not just how a system performs technically, but how reasonably foreseeable human behaviour interacts with that system.

For manufacturers, the lesson is clear: liability exposure does not depend solely on whether the code executes as intended, but also on how average drivers interpret and respond to automation cues. Designing robust driver-monitoring systems, issuing timely software updates to address safety concerns, and aligning marketing language with regulatory classifications of driver-assistance levels are all essential elements of a defensible risk posture. In the EU context, the interplay between vehicle safety regulations, the AI Act (where AI features function as safety components), and the revised Product Liability Directive will further shape how courts assess negligence in Autopilot-style cases.

SAE automation levels and corresponding liability shifts

The SAE International taxonomy of driving automation levels (from Level 0 to Level 5) has become a conceptual anchor for discussions about autonomous vehicle liability. At lower levels (0–2), the human driver retains primary responsibility for monitoring the environment and executing driving tasks, with automation limited to driver assistance. In this paradigm, civil liability continues to resemble traditional traffic accident analysis: drivers are typically held liable for errors, with product liability claims arising only where a clear defect in brakes, steering, or ADAS functionality can be proven.

At Levels 3–5, however, the dynamic reverses. Once the system—not the human—is responsible for monitoring the driving environment under certain conditions, the rationale for assigning primary fault to the driver weakens. If a Level 3 system fails to execute a safe fallback manoeuvre or fails to hand control back to the driver with sufficient warning time, courts are more likely to view the harm as a manifestation of system defectiveness or inadequate human–machine interface design. At Levels 4 and 5, where vehicles are expected to operate without human drivers in defined operational design domains, manufacturers and system operators will shoulder much of the liability burden.

In practice, this shift does not mean drivers or fleet operators will never be held liable. Misuse of autonomous systems—such as tampering with driver-monitoring cameras or deliberately operating vehicles outside their certified domains—can still constitute negligence. But as automation becomes more capable and pervasive, the legal default is likely to trend towards treating the autonomous system as the “reasonable driver,” with liability focusing on whether its performance and safeguards met applicable safety standards. Regulators and insurers are already exploring models where civil liability gradually migrates from individual motorists to manufacturers, fleet operators, and mobility service providers as the automation level rises.

Data recorder requirements and evidential burden in collision litigation

As autonomous vehicle functionality expands, event data recorders (EDRs) and broader “black box” systems play a central role in reconstructing what actually happened during a collision. Modern vehicles can log steering inputs, acceleration, braking, sensor readings, perception outputs, and software version data milliseconds before impact. This wealth of information is invaluable for determining whether a human or the automated system was in control, whether warnings were issued, and whether the system behaved in line with its design specifications.

Legislators and regulators are increasingly mandating such data recording capabilities for vehicles equipped with advanced driver-assistance systems and higher-level automation. In the EU, type-approval and vehicle safety regulations intersect with the AI Act’s event-logging requirements where AI is a safety component. These requirements, in turn, influence civil litigation dynamics: plaintiffs may request access to vehicle logs, over-the-air update histories, and even backend server data to substantiate claims of defectiveness or negligent operation. Failure by manufacturers to preserve or disclose relevant data can lead courts to draw adverse inferences or apply presumptions of defectiveness, echoing the disclosure rules in the revised Product Liability Directive.

For organisations involved in autonomous mobility, robust data-governance frameworks are therefore not only a technical or privacy concern, but a liability one. Clear retention policies, secure storage, and well-defined procedures for responding to court orders or regulatory requests help ensure that relevant evidence is available—and that disclosure can be managed without unduly compromising trade secrets or personal data protection obligations. From a strategic perspective, comprehensive and accurate logs can be a powerful defence tool, demonstrating that the system behaved as designed and that any harm arose from external factors or misuse.

Insurance coverage gaps for level 4 and level 5 autonomous systems

Traditional motor insurance models assume that human drivers are at the centre of risk assessment and premium calculation. As we move towards Level 4 and Level 5 autonomous vehicles, this driver-centric approach starts to break down. If a ride-hailing fleet of fully autonomous shuttles operates in a city centre, who is the “driver” for insurance purposes—the manufacturer, the software provider, the fleet operator, or the city authority authorising deployment? Insurers must rethink underwriting models, policy wording, and subrogation strategies in light of this new reality.

Several jurisdictions are experimenting with solutions that shift primary liability from individual drivers to insurers or manufacturers for autonomous vehicles, with insurers then pursuing recovery from responsible parties further up the supply chain. However, significant coverage gaps remain, particularly for Level 4 pilots operating in restricted domains, mixed fleet scenarios where vehicles can switch between manual and autonomous modes, and cross-border operations where different liability presumptions apply. Organisations deploying such systems should carefully review whether existing motor, product liability, cyber, and professional indemnity policies adequately address AI-related risks and software failures.

Closing these gaps will likely require bespoke policy endorsements and closer collaboration between manufacturers, operators, and insurers. Clear contractual allocations of risk, minimum insurance requirements in deployment agreements, and transparent incident-reporting mechanisms can help ensure that victims are compensated promptly while preserving avenues for recourse against responsible actors. As with other aspects of civil liability in the digital age, proactive planning is far more effective than attempting to retrofit coverage after an incident has exposed unforeseen vulnerabilities.

Medical device innovation and clinical negligence in digital health technologies

Healthcare is one of the sectors most profoundly reshaped by digital technologies, from robotic surgical platforms and AI-assisted diagnostics to remote patient monitoring and telemedicine services. These innovations promise earlier detection, greater precision, and improved access to care—but they also complicate traditional fault lines in medical malpractice and product liability. When harm occurs, is the root cause a clinician’s breach of the standard of care, a defective medical device, flawed training data, or a combination of all three?

Regulators and courts are gradually constructing a layered accountability model that mirrors the dual structure seen in AI product regulation more generally: safety and performance requirements for devices and software on the one hand, and professional standards for clinicians on the other. For hospitals, manufacturers, and digital health startups, understanding how these regimes interact—particularly in cross-border contexts where patients, providers, and technology suppliers may be located in different jurisdictions—is crucial to managing both legal risk and clinical governance.

Da vinci surgical system malfunctions and operator liability boundaries

The Da Vinci Surgical System, a widely used robotic-assisted platform, illustrates how responsibility can be distributed between device manufacturers and medical professionals. Over the past decade, reports of instrument malfunctions, software glitches, and user-interface challenges have sparked litigation alleging injuries during minimally invasive procedures. Plaintiffs have argued that design flaws, insufficient warnings, or inadequate training contributed to adverse events, while manufacturers have frequently responded that outcomes were primarily due to surgical error or deviation from recommended protocols.

Court decisions in these cases often turn on detailed factual analyses of training records, device logs, and intraoperative documentation. Where hospitals and surgeons can demonstrate comprehensive training on the system, adherence to manufacturer guidelines, and prompt response to device alerts, the focus may shift towards potential product defects or inadequate warnings. Conversely, where evidence shows that operators ignored alarms, failed to convert to open surgery when indicated, or used off-label techniques, liability is more likely to fall within the realm of clinical negligence.

For healthcare organisations, clarifying operator liability boundaries requires robust credentialing processes, documented training curricula, and ongoing competency assessments for robotic surgery. Manufacturers, for their part, can mitigate risk by providing clear and updated instructions for use, realistic marketing about system capabilities, and effective post-market surveillance to identify emerging safety patterns. In a liability landscape where both human and technological factors intertwine, collaboration between device makers and clinical teams is essential to ensure that responsibility is fairly allocated and that patient safety remains central.

FDA 510(k) clearance process and manufacturer due diligence standards

In the United States, many innovative medical devices and software as a medical device (SaMD) products enter the market through the FDA’s 510(k) clearance pathway, which allows approval based on “substantial equivalence” to a predicate device. While efficient, this process has sometimes been criticised for allowing risks associated with novel digital functionalities to be underappreciated, especially where AI or adaptive algorithms are involved. In subsequent civil litigation, plaintiffs may argue that manufacturers relied too heavily on predicate comparisons and failed to conduct adequate independent validation of new features.

From a civil liability standpoint, regulatory clearance is not an absolute shield against claims of defectiveness or failure to warn. Courts may consider FDA compliance as evidence of due care, but they also examine whether manufacturers performed robust clinical evaluation, usability testing, and post-market risk management proportionate to the product’s complexity and potential for harm. For AI-driven devices, due diligence increasingly includes continuous performance monitoring, drift detection, and real-world evidence collection to confirm that algorithms perform reliably across diverse patient populations and clinical settings.

Manufacturers seeking to reduce litigation exposure should treat the 510(k) process as a baseline rather than a ceiling for safety assurance. Detailed documentation of testing methodologies, risk–benefit analyses, change-control procedures, and post-market surveillance findings can be invaluable in defending against claims that a device was defective or that warnings were inadequate. In the EU, similar expectations flow from the Medical Device Regulation (MDR), which imposes more demanding clinical evidence and post-market vigilance requirements for software-based devices, particularly those involving AI.

Telemedicine malpractice claims across jurisdictional boundaries

Telemedicine platforms and remote consultation services have expanded rapidly, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling patients to access care across regional and national borders. While these technologies improve accessibility, they complicate core questions in medical negligence law: where is the care legally provided, which jurisdiction’s standard of care applies, and which courts have authority to hear claims? When a clinician in one country uses a telehealth platform hosted in another to advise a patient in a third, the resulting liability matrix can be intricate.

Courts typically examine factors such as the patient’s location, the clinician’s licensure, contractual jurisdiction clauses, and applicable conflict-of-law rules to determine which legal regime governs a telemedicine malpractice claim. Some jurisdictions treat teleconsultations as occurring where the patient is located; others focus on the provider’s place of practice. Meanwhile, platform operators may face claims related to system outages, data breaches, or interface design that allegedly contributed to misdiagnoses or treatment delays. This multiplicity of actors and legal forums underscores the importance of clear terms of service, informed consent processes tailored to telehealth, and robust cross-border compliance strategies.

Healthcare providers and digital health companies can mitigate these jurisdictional risks by carefully defining service territories, ensuring clinicians are appropriately licensed in target markets, and adopting standard-of-care guidelines that reflect both local regulations and international best practices. Clear communication with patients about the nature and limitations of telemedicine—such as when in-person examination is required and what to do in emergencies—also helps manage expectations and reduce the likelihood of disputes. As telemedicine continues to mature, we can expect more detailed regulatory frameworks and professional standards to emerge, providing clearer guidance on cross-border liability allocation.

Ai-assisted diagnostic tools: shared liability between clinicians and developers

AI-assisted diagnostic tools, from radiology triage systems to pathology image analysis algorithms, epitomise the “augmented intelligence” model in healthcare. These tools are typically designed to support, not replace, human clinicians by flagging suspicious findings, suggesting differential diagnoses, or prioritising cases. Yet when an AI system misses a tumour on a scan or generates a misleading recommendation that a clinician follows, determining who is responsible becomes complex. Was it a negligent misinterpretation by the doctor, a defective algorithm, or a failure in how the tool was integrated into clinical workflow?

Most legal systems continue to view clinicians as the ultimate decision-makers responsible for applying professional judgment, which means they remain the primary defendants in many malpractice suits. However, as AI tools become more pervasive and sophisticated, plaintiffs increasingly name software developers and device manufacturers as co-defendants, alleging design defects, inadequate validation, biased training data, or insufficient warnings about performance limitations. Where hospitals or health systems customise models, retrain algorithms on local data, or alter default thresholds, they too may be drawn into shared liability on the basis of “substantial modification.”

To navigate this shared responsibility, stakeholders should adopt transparent performance reporting, clear labelling of intended use and limitations, and robust clinical governance around AI adoption. Clinicians need training on how to interpret AI outputs, when to override them, and how to document their reasoning in medical records. Developers should provide explainability features where feasible, confidence scores, and guidance on appropriate contexts for use. When each actor understands and fulfils their respective duties, the risk of harmful reliance on AI—and subsequent liability—can be significantly reduced.

Internet of things security failures and duty of care obligations

The “Internet of Things” (IoT) connects billions of devices—from smart thermostats and wearables to industrial sensors and medical implants—bringing efficiency and convenience but also creating an expanded attack surface for cyber threats. Security vulnerabilities in these devices can lead not only to data breaches, but also to physical harm, property damage, and systemic disruptions. In civil liability terms, this raises fundamental questions about the scope of manufacturers’ and service providers’ duty of care, particularly when exploited vulnerabilities were foreseeable and preventable.

As regulators sharpen their focus on cybersecurity as an integral aspect of product safety, courts are increasingly likely to treat inadequate security practices as a form of negligence. For businesses developing or deploying IoT products, this means that secure-by-design principles, timely patching mechanisms, and transparent vulnerability management are no longer optional competitive differentiators; they are becoming baseline legal expectations. Failure to meet these expectations can transform what might once have been considered “sophisticated cybercrime” into a foreseeable harm for which civil liability attaches.

Smart home device breaches and foreseeable harm doctrine

Smart home ecosystems—encompassing connected locks, cameras, speakers, and appliances—offer a clear example of how cybersecurity lapses can translate into tangible harm. Incidents where attackers gain access to baby monitors, disable security systems, or use compromised devices as entry points to corporate networks illustrate the real-world risks. When such breaches occur, plaintiffs may argue that manufacturers failed to implement basic security measures, such as strong authentication, secure default settings, or encrypted communications, and that these omissions violated a duty of care owed to consumers.

Under the doctrine of foreseeable harm, courts examine whether a reasonable manufacturer in the same position could have anticipated that poor security design would expose users to specific types of damage. As high-profile IoT breaches become more common and security guidance more widely disseminated, the threshold for what counts as “foreseeable” continues to expand. Features like shipping devices with default passwords, neglecting firmware update mechanisms, or ignoring known protocol vulnerabilities are increasingly difficult to defend as mere oversights rather than negligent design choices.

For organisations operating in the smart home market, implementing systematic threat modelling, regular penetration testing, and coordinated vulnerability disclosure programmes is essential to demonstrate that reasonable steps were taken to mitigate known risks. Clear user guidance on secure configuration, prompt communication about discovered vulnerabilities, and over-the-air patching capabilities further support the argument that a robust duty of care was exercised—even if a sophisticated attacker ultimately succeeded. In a liability environment where foreseeability is evolving rapidly, staying aligned with industry best practices can make the difference between an unfortunate incident and a successful negligence claim.

GDPR article 25 data protection by design requirements

In the European Union, IoT manufacturers and service providers must also grapple with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which embeds security and privacy considerations directly into legal obligations. Article 25 GDPR requires “data protection by design and by default,” meaning that appropriate technical and organisational measures must be integrated into products and services from the outset to ensure that only necessary personal data are processed and that such data are adequately protected. For IoT devices that continuously collect, transmit, and analyse user data, compliance with Article 25 is central to both regulatory and civil liability exposure.

Regulatory enforcement actions under GDPR—especially where significant fines are imposed—can be powerful evidence in subsequent civil claims alleging data protection breaches and associated harm. Claimants may argue that failure to implement encryption, role-based access controls, or granular privacy settings constitutes not only a regulatory violation but also a breach of the duty of care. As courts across Europe become more comfortable with GDPR-based reasoning, we can expect increasing overlap between regulatory non-compliance and findings of negligence in privacy and cybersecurity litigation.

To reduce this risk, organisations should embed privacy impact assessments, secure development lifecycle practices, and default-minimisation of data collection into their IoT product strategies. Documenting these efforts—through design records, risk assessments, and internal policies—helps demonstrate that reasonable care was taken, even if a breach occurs. By aligning product design with GDPR Article 25 requirements, companies not only reduce the likelihood of enforcement action but also strengthen their defensive position in any parallel civil proceedings.

Mirai botnet precedent and manufacturer cybersecurity responsibilities

The Mirai botnet attacks of 2016, which hijacked hundreds of thousands of insecure IoT devices to launch massive distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) assaults, marked a turning point in how policymakers and industry view connected device security. Many of the compromised devices—such as cameras and routers—were shipped with hard-coded default credentials and lacked straightforward mechanisms for users to change them. While early responses focused on criminal prosecution of the botnet’s operators, attention soon shifted to the systemic role of device manufacturers in enabling such large-scale abuse.

Although Mirai-era civil litigation was limited, the incident has informed subsequent regulatory initiatives and standard-setting efforts. Today, guidance from cybersecurity agencies, industry consortia, and standards bodies routinely emphasises banning hard-coded passwords, implementing secure boot processes, and providing automated update mechanisms for IoT devices. As these expectations crystallise into binding rules—such as the EU’s Cyber Resilience Act and sector-specific security obligations—the argument that manufacturers bear responsibility for foreseeable exploitation of known weaknesses becomes much stronger.

From a liability perspective, Mirai functions as a cautionary tale: once a particular attack vector has been widely publicised, continuing to deploy devices with the same weakness can be characterised as reckless rather than merely negligent. Manufacturers who fail to internalise lessons from major cybersecurity incidents risk facing not only regulatory penalties but also civil claims alleging that they ignored clear warnings about systemic vulnerabilities. Incorporating up-to-date security baselines into product design and lifecycle management is therefore an essential part of navigating IoT-related civil liability in the digital age.

Blockchain technology disputes: smart contract bugs and legal recourse

Blockchain and distributed ledger technologies have introduced new paradigms for recording transactions, enforcing agreements, and managing digital assets. Smart contracts—self-executing code running on decentralised networks—promise automated, trustless execution of obligations without traditional intermediaries. Yet as high-profile exploits and protocol failures have demonstrated, bugs or design flaws in smart contracts can lead to substantial financial losses, raising challenging questions about liability, remedy, and jurisdiction in a decentralised environment.

Unlike conventional contracts, which allow courts to interpret ambiguous language and order equitable remedies, smart contracts often execute deterministically according to their code, regardless of parties’ subjective intentions. This “code is law” ethos clashes with legal systems that prioritise fairness, good faith, and consumer protection. When an exploit drains funds from a decentralised finance (DeFi) protocol or a governance failure leads to unintended token transfers, affected users may find themselves navigating a complex intersection of contract law, tort principles, securities regulation, and platform governance rules.

The DAO hack and immutability versus equitable remedies

The 2016 hack of The DAO, an early decentralised investment vehicle built on Ethereum, remains a touchstone for discussions about blockchain liability and immutability. Exploiting a vulnerability in The DAO’s smart contract, an attacker siphoned off millions of dollars’ worth of Ether. Although the transaction was technically valid under the contract’s code, many participants argued that it violated the spirit and intent of the arrangement. In response, the Ethereum community controversially implemented a hard fork to reverse the effects of the hack, effectively prioritising equitable considerations over strict code immutability.

From a legal perspective, The DAO episode illustrates that immutability is not an absolute barrier to remedy. Courts and regulators can, in principle, recognise that a transaction, while valid on-chain, is void or voidable under off-chain legal standards—for example, due to fraud, mistake, or unconscionable conduct. The practical difficulty lies in enforcement: even if a court orders restitution, enforcing that order against pseudonymous actors and decentralised protocols can be highly challenging. As a result, much of the remedial power in blockchain ecosystems still rests with protocol governance mechanisms and community norms rather than traditional judicial processes.

For developers and organisers of blockchain projects, The DAO serves as a reminder that rigorous code auditing, formal verification where feasible, and clear risk disclosures are essential to managing both community expectations and legal exposure. Including governance mechanisms that allow for controlled intervention in catastrophic scenarios—such as emergency pause functions or upgrade paths subject to transparent voting—can provide a bridge between on-chain execution and off-chain equitable principles, making it easier to align decentralised systems with prevailing liability norms.

Code-as-law limitations in decentralised finance protocol failures

Decentralised finance has expanded rapidly, with protocols offering lending, trading, and derivatives services governed by smart contracts rather than traditional financial intermediaries. While advocates emphasise transparency and predictability—“the code does what it says”—real-world incidents reveal that users often lack the expertise to fully understand protocol risks. When a DeFi protocol suffers a flash loan attack or suffers from a critical bug, platform operators may argue that users accepted the inherent risks by interacting with open-source code, while users contend that material risks were not adequately disclosed or managed.

Legal systems are beginning to probe the limits of the “code-as-law” narrative. Courts may treat user interfaces, white papers, and marketing materials as representations that shape reasonable expectations, particularly for retail participants. If these materials suggest that a protocol is “tested,” “secure,” or “audited,” but in reality key vulnerabilities remain, claims based on misrepresentation, negligent design, or failure to warn may arise. Additionally, where identifiable developers or governance entities retain substantial control over protocol parameters or upgrades, arguments that a system is fully decentralised and beyond anyone’s responsibility lose credibility.

To mitigate liability, DeFi developers and DAO governance bodies should adopt transparent disclosure practices about known risks, audit status, and upgrade procedures. Implementing bug bounty programmes, engaging reputable auditors, and promptly addressing disclosed vulnerabilities are practical steps that both enhance security and strengthen a potential defence against negligence allegations. As regulators increasingly scrutinise DeFi activities under financial services and consumer protection laws, aligning protocol governance with recognised standards of care will become ever more important.

Jurisdictional challenges in cross-border cryptocurrency tort claims

Cryptocurrency and blockchain networks are inherently global, with nodes, users, and developers distributed across multiple jurisdictions. When a platform failure, hack, or misleading token sale leads to losses, determining which courts have jurisdiction and which law applies is often complex. Plaintiffs may seek to file claims in forums perceived as more favourable, while defendants argue that decentralisation and lack of physical presence limit a court’s authority. Traditional private international law doctrines—such as place of harm, domicile of parties, and choice-of-law clauses—must be adapted to a context where transactions and actors are often pseudonymous and borderless.

Courts have begun to apply pragmatic approaches, sometimes asserting jurisdiction based on the location of affected users, the presence of local marketing activities, or the operation of fiat on-ramps and exchanges within their territory. In some cases, smart contract or platform terms of use include explicit jurisdiction and governing law clauses, providing a degree of certainty—but these clauses may be challenged where consumers are involved or where regulatory public policy is at stake. As a result, multi-jurisdictional litigation and parallel proceedings are not uncommon in major blockchain disputes.

For blockchain projects, clarifying legal touchpoints in target markets is essential. This includes assessing whether activities trigger local licensing or registration requirements, drafting clear and enforceable terms of use, and considering where key governance or operational functions are located for jurisdictional purposes. Proactive legal structuring—such as establishing entities in jurisdictions with well-developed digital asset frameworks—can help reduce uncertainty and facilitate more predictable resolution of cross-border tort claims.

Data breach notification timelines and compensation frameworks under emerging legislation

Data breaches have become a defining risk of the digital era, affecting organisations across sectors and jurisdictions. Legislators worldwide have responded by introducing mandatory breach notification regimes and, in some cases, explicit compensation frameworks for affected individuals. These laws aim to ensure timely disclosure, enable individuals to take protective measures, and provide pathways to redress where inadequate security measures contributed to the incident. For organisations, compliance with notification timelines and evolving standards of care in data protection is now a central component of civil liability management.

In the European Union, GDPR remains the cornerstone of breach notification obligations, requiring controllers to notify supervisory authorities within 72 hours of becoming aware of a personal data breach, unless the breach is unlikely to result in risk to individuals’ rights and freedoms. Similar regimes exist in many other jurisdictions, with varying timelines and thresholds. Failure to comply can result not only in regulatory fines but also in civil claims, including collective actions, alleging that delayed notification exacerbated harm by preventing timely mitigation steps such as password changes or credit monitoring.

Emerging legislation increasingly couples notification duties with clearer compensation rights for individuals affected by data breaches. Under GDPR, data subjects can claim material and non-material damages resulting from violations, and several high-profile cases have tested the boundaries of what constitutes compensable distress. Elsewhere, dedicated privacy and cybersecurity statutes establish statutory damages or streamlined claims processes, particularly in consumer contexts. As collective redress mechanisms gain traction, organisations may face significant aggregate exposure even where individual losses are relatively small.

To navigate this evolving landscape, organisations should invest in comprehensive incident response planning, including clear internal escalation paths, pre-drafted notification templates, and relationships with forensic experts and legal counsel. Rapid assessment of breach scope, affected data categories, and potential harm is critical to meeting statutory timelines while ensuring that notifications are accurate and not misleading. Additionally, offering remediation measures—such as credit monitoring, identity theft protection, or dedicated support channels—can both reduce actual harm and demonstrate good faith, potentially influencing regulatory and judicial assessments of liability.

Ultimately, data breach liability in the era of technological innovation hinges on whether organisations can show that they took reasonable, risk-appropriate measures to protect the data entrusted to them and responded promptly and transparently when incidents occurred. As regulatory expectations and industry best practices continue to evolve, staying aligned with emerging standards—rather than merely meeting outdated minimum requirements—will be key to reducing both legal exposure and reputational damage.